This past spring, we, along with several other members of the press, were invited to Wellington to visit the set of The Hobbit,

and at long last, we can reveal some of what we saw and learned,

including more details on how Peter Jackson is expanding J.R.R.

Tolkien's original story, how Gandalf will spend his time away from the

main party, the Dwarves' individual personalities and backstories, and

just how all this Middle Earth craziness is being filmed. Many, many

spoilers below.

Expand

Expand

No

cameras were permitted at Stone Street Studios and Weta during this

particular set visit. Instead, we have sketches from my notebook and

illustrations I made based on my sketches and notes. (Those of you who

have read my critiques of other people's artwork get to enjoy my

terrible sense of perspective.) Since the sketches were assembled

hastily, you'll have to take everything here as a rough approximation of

the actual visuals. (Thorin's sword, for example, may look slightly

different from my illustration below.) But we've done our best to bring

you a small taste of the visual experience of visiting the set.

So what is going on in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey? Again and again, we heard that The Hobbit films will maintain the somewhat lighter, adventure story tone that separates it from Lord of the Rings

while fleshing out the connections between the two stories and adding a

bit more individuality to the characters. And it's all being achieved

with close attention to the details of concept design, costuming, makeup

and prosthetics, prop creation and special effects. Here's what we

learned about the first film in The Hobbit trilogy from the cast and crew:

The Ballad of Bilbo Baggins

The journey of The Hobbit starts, of course, with our titular Hobbit, Bilbo Baggins, portrayed by Martin Freeman. Despite Jackson's expansion of The Hobbit story to connect it to Lord of the Rings,

Bilbo's transformation from timid Hobbit into hero remains at the

center of the films. And Gandalf is the one who gives him that first

nudge. Jackson explains:

[Gandalf] just remembers this young Bilbo Baggins as a young child who was the one Hobbit that he sees that loves adventure likes danger, loves scary stories. That has a more outgoing spirit, and when he wants a hobbit to be a burglar on this adventure he returns to Hobbiton many years later and he finds Bilbo. He deliberately hunts down Bilbo, because that's the hobbit who he thinks would be the best one to pick for this. He's appalled and shocked to find at the end of eighteen years Bilbo's become stuffy, and ultra conservative, and not at all like the little boy that he remembers. So that's the beginning of their relationship really.

So Gandalf

forces Bilbo onto this mission with the Dwarves, and throughout the

films, the Hobbit will find himself confronted with people who have

warring agendas. Bilbo doesn't have these same sorts of motivations, but

he has somehow found himself on an adventure involving all these

factions and he has deal with them. By handling these personalities and

their distinct interests—and encountering a few especially dangerous

foes—Bilbo will gradually grow into his heroic role, and that unlikely

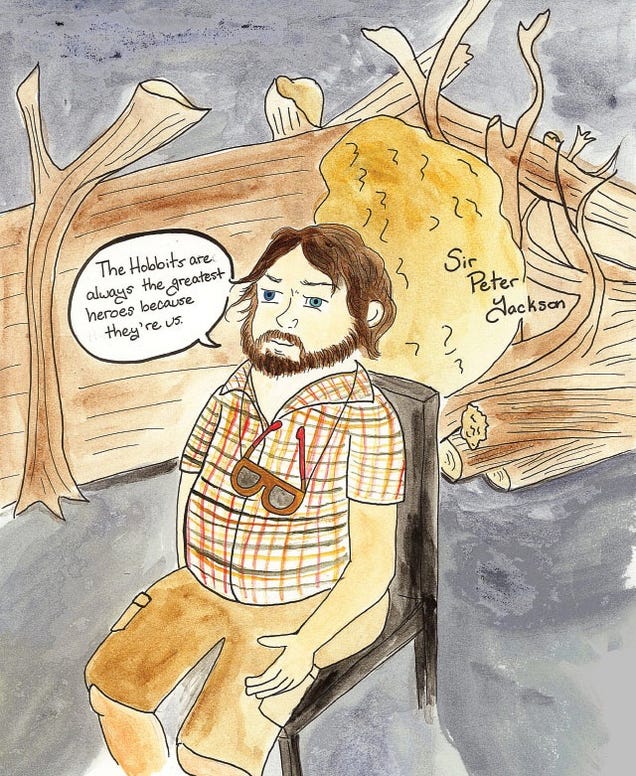

hero is what Jackson finds so appealing about Bilbo's story:

The Hobbits are always the greatest heroes 'cause they're us, they're the unlikely hero who is thrust into this incredible danger and they have no choice but to get the goodness within themselves and the strength within themselves and try to survive and get through it, so they're always the most interesting heroes. They're not flawed, they're just unlikely heroes. They're not the sort of person you would really think would be able to take on a dragon, but when you see them actually doing that, I find that sort of heroism in films really interesting. Legolas is just a hero. I don't identify myself with Legolas that much. Just go and let Orlando do his thing and it's great for the movie [Note: Not necessarily the first Hobbit movie]. It's good.

Freeman,

for his part, says that he "wasn't steeped in" Tolkien during his life.

But he wanted to make the part of Bilbo his own, rather than basing his

performance on Ian Holm's older Bilbo in Lord of the Rings. Freeman says, however, that he did study Holm's performance closely for certain key points during filming of The Hobbit. (He wouldn't say where in the films those key points crop up.)

And will Bilbo be feeling the effects of the One Ring during the films? Tolkien wrote The Hobbit two decades before Lord of the Rings and hadn't yet fleshed out the Ring's backstory and nature. Jackson explains that the Ring won't be quite as dastardly in The Hobbit films as in Lord of the Rings:

The way that it's rationalized, and I think people in the Tolkien world have rationalized it as the ring doesn't really gain its power until Sauron comes back and actively starts to look for it, so it's asleep for a while and in the days of Frodo it's getting very agitated and it wants to find its way back to Sauron.

There will,

however, be nods to the Ring's power. The first time Bilbo puts on the

Ring, says Jackson, it will seem to be a mere magic ring, but he'll

experience more of the Ring's effects each time he uses it. Martin says

that the Ring will have a recognizable pull on Bilbo, but that pull will

"take a different turn" than it does in Lord of the Rings. Freeman notes that even though the tone of The Hobbit is a bit lighter than Lord of the Rings:

But it doesn't mean the stakes aren't there. It definitely still has to matter that he is in possession of this thing. And I think a lot of the time, even he doesn't realize why he wants to hold onto it so much, but there is an unspoken hold that it has on him, an unconscious hold.

Jackson

says that we'll see some of the Shadow World when Bilbo slips on the

Ring, but it won't be so nightmarish. It's in its infancy, before

attracting the Eye of Sauron.

Gandalf's Journey

Meanwhile,

Gandalf (Sir Ian McKellan) will vanish and reappear throughout Bilbo's

journey, but unlike in the novel, we will get to see where Gandalf

disappears to. As we've noted before, this is no great surprise since Tolkien explained what Gandalf was doing during those missing moments in the appendix to Return of the King.

When Gandalf leaves the Dwarves, we learn why he throwing his support

behind Thorin's quest. (Tolkien explains the relationship between

Thorin's quest and the White Council in that appendix.) While the

adventure story sits at the core, McKellan explains, "There will be the

politics of Middle Earth going on in the background as a support."

Not only do

we zoom in on the relationship between Gandalf and Bilbo, but on the

relationship between Gandalf and Thorin as well. Gandalf wants to keep

an eye on all the Dwarves, but his feelings toward Thorin, whom McKellan

describes as "a bit out of control and not easily managed," are

especially strained. One of the films' tensions will be whether Thorin

will do things Gandalf's way.

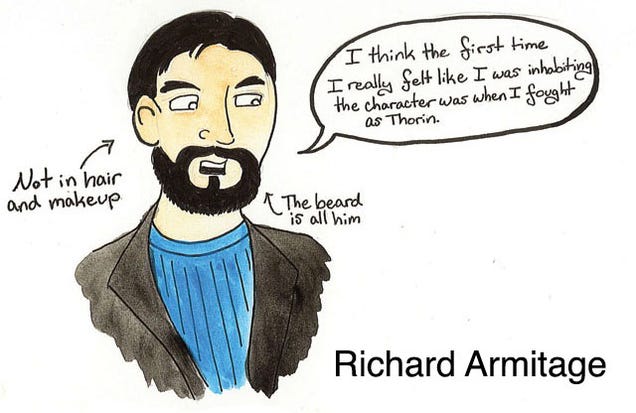

Richard

Armitage, who plays Thorin, says that the Dwarves need Gandalf because

he possesses Thror's map and key, but also that Gandalf "hoodwinked"

Thorin into this quest, starting their relationship off on an

antagonistic foot. While Thorin agrees to take on Bilbo as the party's

thief, he's none too pleased about it, and, Armitage continues, would

rather throw off the yoke of Gandalf's leadership:

I think Thorin is trying to prove that Gandalf isn't correct, and most of his assumption is that he's trying to usurp his leadership. When Gandalf isn't there, Thorin really becomes a leader, and when [Gandalf] turns up, [Thorin] has to be subservient, and it's not something that he likes at all.

McKellan

says that Gandalf does lose his temper with Thorin at one point, but in

other parts of the films, he gets to play the mischievous trickster from

the book.

Meet the Dwarves

Jackson

told us, "Bilbo is the soul of the story, but the dwarves and their

wanting to reclaim their homeland is very much the heart of the story."

In the original book, the Dwarves are fairly indistinguishable from one

another, except for their leader Thorin Oakenshield. But in the films,

each Dwarf has a distinct personality, a backstory, and a role in the

group. They have different reasons for joining Thorin on his quest, and

they have very different relationships with one another and with Bilbo.

The

Dwarves' quest to repossess the Arkenstone and retake their ancestral

home is expanded as well. Gold is still a concern for these Dwarves, but

it's not necessarily their major concern. For some of the Dwarves in

Thorin's party, the pain of being forced from Lonely Mountain is still

fresh. But even the younger Dwarves have decided to come on what many

believe is a fool's errand to reclaim the mountain. Armitage elaborates:

[T]his particular group of Dwarves, only thirteen of them have come out on this quest. Everyone else turned their backs and said, "No, no, no, leave it alone. Stay away from that mountain." So it really is about thirteen survivors that are going to attempt to do something which people have dissuaded other Dwarves from doing.

We'll also

be seeing younger versions of Thorin and his warrior compatriot Dwalin,

suggesting that we may see flashbacks to the Dwarves' exile from Erebor

and/or the Battle of Azanulbizar in Moria.

Expand

Expand

Richard

Taylor, co-founder and co-director of Weta says that creating thirteen

distinct looks for the thirteen main Dwarf characters was a challenge,

"But a wonderful challenge all the same." Each Dwarf has a distinct

silhouette, as well as small details that point to their station in life

and their personal histories.

Jackson describes Thorin as "an anti-hero":

He's become so obsessed with what he believes to be the right thing that he crosses a boundary in way, with the dragon sickness and things.

Armitage is

quick to point to Thorin's background; he is one of the few members of

his party who have experienced the "holocaust" that was the Dwarven

exile from Erebor. (Armitage says he used the bombing of Hiroshima as an

inspiration for the devastation caused by Smaug.) He still carries with

him the trauma of Smaug coming to Lonely Mountain—as well as the heavy

responsibility of trying to reclaim his ancestral home:

Yeah, I think knowing that his father and his grandfather have been touched by this dragon sickness which doesn't necessarily affect all Dwarves, but some Dwarves are susceptible to it. It's this attraction to gold which becomes their downfall, has always been at the back of his mind. And I think the burden of taking his people back to their homeland, which is so massive, makes him a lonely figure, I think. Knowing that his grandfather failed, and his father failed, so if he doesn't do it, there's no other member of his line that will ever do this. So he will continue through history as the king that failed to achieve the potential for his people.

Thorin's

greatest fear, says Armitage, is failure, "And there's many

opportunities for him to fail on this quest." He sees Thorin as a

primarily melancholic character, although he suspects gold might perk up

the King in Exile.

Six-foot-two

Armitage never saw himself playing a five-foot-two Dwarf, but after

playing Thorin for so long, he understands that the Dwarves don't think

of themselves as small. "They're compensating for the fact that they are

a secret forbidden race that were nearly destroyed." And, though Thorin

is supposed to be an old character—older even than Gandalf (in

Armitage's words, perhaps meaning relatively as opposed to

chronologically)—he felt Thorin come to life as a warrior:

I needed him to be heroic on the battlefield and somebody that still has a potential to rise to that state of brilliance on a battlefield, even though it's like— He's like a flame that's fluttering, and has nearly been extinguished, but it has the potential to re-ignite. It's like a dying flame when you first meet him, but he still has to be a flame.

Taylor says

that Thorin presented the greatest design challenge, both in terms of

of his prosthetics and his costume. The Weta team wanted to capture the

character's nobility as well as his inner darkness and world weariness.

Armitage's prosthetic forehead is extremely thin, according to Taylor,

"probably less than point-

one of a millimeter thick on the eyebrows," ensuring that Armitage can convey a full range of emotions with his face.

one of a millimeter thick on the eyebrows," ensuring that Armitage can convey a full range of emotions with his face.

Expand

Expand

Five

sets of brother and cousins from various families accompany Thorin on

his quest. The actors were encouraged to bring their own ideas to the

table to develop their own characters as individuals, but those familial

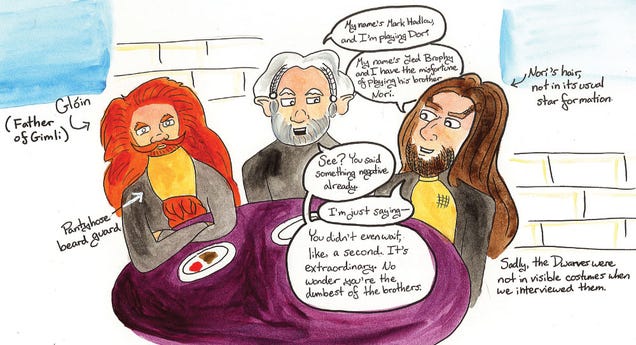

ties are significant. Peter Hambleton, who plays Gloin (son of Groin, brother of Oin, father of Gimli), explains:

[T]here's all sorts of different textures of loyalty, affection, family feuds, family versus family, where our family is a bit suspicious of that gang over there [eyes Dori and Nori].

Mark Hadlow, who plays Dori,

said that when trying to figure out his emotional response in a give

scene, he found it especially helpful to think of whether a particular

situation benefitted his clan or another. Still, the actors said that

when the Dwarves are confronted by an outside threat, they put aside

their differences and join together into a "rock-solid" team.

Regarding

Gloin in particular, Talyor says that when the team was designing

Gloin's look, they used Gimli as their jumping off point. We'll have to

see if he and his son share similar personalities.

Nori

(Jed Brophy), with his wild star-shaped hair and beard, was the most

dramatic silhouette the designers created for the Dwarves. Taylor

acknowledges that it's a pretty wild choice:

And this is where, in an effort to try and find unique and new designs, you walk that very fine knife edge. Some will argue, I have no doubt, that we fell off the knife edge. I'd like to think we're teetering right on it. Because you've got to be bold and you've got to be brave and you've got try these things.

Nori is the middle child in the family of Dori, Nori, and Ori

(Adam Brown). Hadlow and Brophy describe their characters as "Kickass,

killer dwarves with a penchant for stealing stuff." As the oldest child,

Dori tends to boss his younger brothers around. Nori resents it, but

Ori gets the worst of it; Dori mothers him, which Hadlow says, "leads him up the wrong path. It's terrible." He grins.

(To add

insult to injury, Ori wears little purple ribbons his mother plaited

into his hair for his first trip out into the big, bad world.)

Expand

Expand

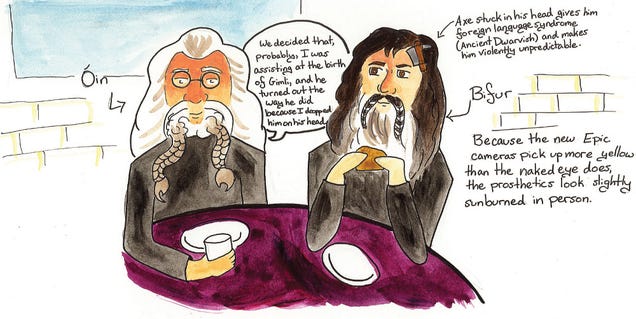

Oin

(John Callen) is the group's apothecary, hauling lotions and potions

and tending to the sick, although Taylor also describes him as one of

the group's "old battlers." Callen offers this tidbit of character

building he developed with Hambleton:

So we thought Oin and Gloin— Gloin is the father of Gimli, and we decided that probably, I was assisting at the birth of Gimli, and he turned out the way he did because I dropped him on his head.

Bifur

(William Kircher) has a somewhat more complicated (not to mention

tragicomical) backstory. Poor Bif has a goblin axe buried in his skull,

and since we're in a pre-surgical world, whoever was tending to him

decided to leave it in there. Bifur is a toymaker and normally a gentle

soul, but that axe has left him with two rather pronounced problems:

First, he suffers from a sort of foreign language syndrome, and can

speak only an ancient version of Dwarvish that no one else can

understand. Two, he becomes at times extremely violent, forcing whomever

is near him to wrench the axe until he becomes docile again. It's no

great surprise that he's looking for the fellow who tried to chop his

skull into firewood.

Expand

Expand

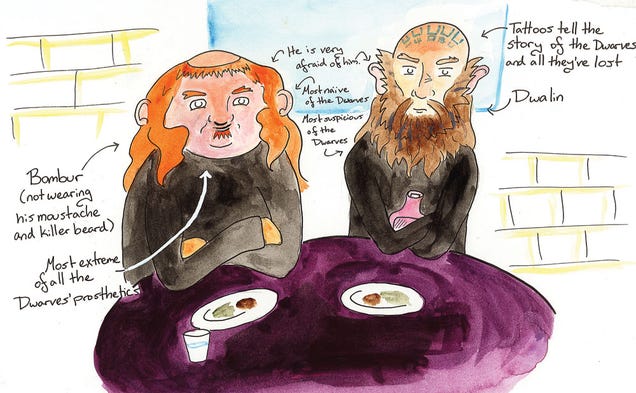

Bombur (Stephen Hunter) is the brother of Bofur

(Jimmy Nesbitt) and cousin of Bifur. The -ur Dwarves are peasant

farmers. "[T]o us it still means quite a lot to go and take over the

mountain," Hunter says, "but we're just going along for the ride."

Bombur is quite naïve, and doesn't know what to expect on this journey,

but don't underestimate him. He can use his beard—which is braided into

an enormous loop—as a weapon. He throws it over his enemies' heads,

pulls them into his massive girth, and strangles them. Otherwise, he

mostly cooks. While other Dwarves carry heavy armor and weapons, Bombur

carries a tiny bag and his trusty ladle.

Bombur is quite terrified of Dwalin (Graham McTavish), as well he should be. Dwalin is the veteran warrior, and he, like his brother Balin

(Ken Stott) and Thorin, witnessed Smaug's arrival in Erebor. Dwalin

realizes that this trip is going to be much more harrowing than the

young Dwarves expect. He's also a particularly violent character.

Dwalin has

taken up this quest in order to reclaim the homeland and restore the

honor of his people. The tattoos on his head and arms are an illustrated

history of the Dwarves, including their defeats at Erebor and Moria, a

permanent reminder of all the Dwarves have lost. He grew up with Thorin

and is staunchly loyal to his lord. His belief is that you must show

undivided loyalty or else you're an enemy. It's no wonder that he

believes everyone is an enemy until proven otherwise. When Bilbo shows

up and Thorin is less than pleased to have him join their company,

Dwalin shares his lord's displeasure. Bombur and Bilbo, on the other

hand, get on quite well.

McTavish

contributed an interesting bit of Dwalin lore. He recalled that Emily

Brontë had two hounds named "Grasper" and "Keeper," and decided that

they would make great names for Dwalin's twin axes. ("That he grasps

your soul with one axe and keeps it with the other," adds McTavish.) He

suggested it to Jackson, and now the names are inscribed on the axes in

Elvish.

Everyone

seemed to agree that Jimmy Nesbitt has the best singing voice. And yes,

the Dwarves do sing the plate-throwing song. Much dinnerware was harmed

in the making of this film.

What about Gollum?

We didn't

get to hear much about Gollum, especially with Andy Serkis busily

directing the second unit. (We got to watch as he studied a scene in one

of the later films and offered feedback to the actors.) But Martin

Freeman shared his experience working with Serkis during his first weeks

on the films:

Well, the first week or two even, maybe, was the Gollum's cave scene for me. That was the first day on set, so I was working with Andy as Gollum, which in itself is interesting. Fascinating as a baptism of fire. But friendly fire, because he's so good, that character is so beloved, and he knows that character, obviously, as well as anybody knows anything. So you feel safe, and you feel like it's an interesting way of— In a way, I preferred a scene that was more like a ten-minute theater scene than if it had been this scene, or just a running scene, or exploding cars.

We look forward to seeing how Serkis handles Gollum's riddles.

Matt

Aitken, visual effects superviser at Weta Digital, says that the digital

crew has been revisiting how Gollum works "under the hood." While they

haven't made tweaks to the character's physical appearance, Aitken says

that his digital body will behave more naturally and realistically.

What to wear in Middle Earth

Expand

Expand

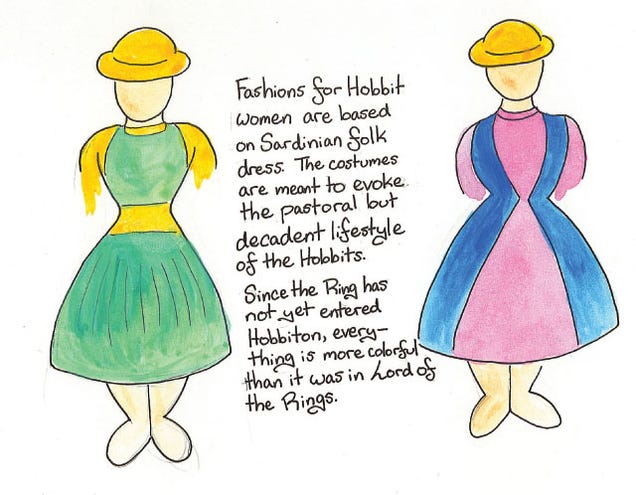

How

do you figure out how Bilbo Baggins dresses? Peter Jackson figured, why

not look at Tolkien himself? Bilbo's country gentleman attire, notably

his jacket and his smoking pipe, have their origins in the author's own

accoutrements. Additional costume designer Bob Buck explained how that

thread extended out into a whole world of Hobbit wear. The Hobbits, he

noted, are a simple, pastoral people, but one whose lives are marked by

frequent celebrations, great food, and beautiful flowers. The costumes

needed a simplicity, but one that fit with the Hobbits' decadent

lifestyle.

The costume

team decided to draw on 18th-century Sardinian folk dress for the

Hobbit women, although the team wanted their wardrobe not to reflect a

specific era but to help them build a fashion world. The boning in the

torsos of the dresses, for example, let them mold the body shapes of

Hobbit women. Gathered, puffy sleeves made the women seem rounder. These

visual tricks made the actresses appear in proper proportion, even when

they donned those giant Hobbit feet.

Also coming to Hobbiton: color. Buck says that this past version of Hobbiton will be more colorful than what we saw in Lord of the Rings:

And one of my theories about why we also are more colorful is because the Ring hadn't actually been in Hobbiton now. In The Lord of the Rings, the Ring had been there, and had been tucked away in an envelope, tucked away in a special chest or whatever. But the evil and the menace, and the bad magic that that emanated, I think sucked the life and the color out of Hobbiton.

Buck calls

Hobbiton "a Sunday best sort of world." Different Hobbits have different

types of outfits based on their status and occupation: farmers,

shopkeepers, rich folk, but for Bilbo they wanted to stick to a

"gentlemanly-ness" and "Tolkien-ness." But Bilbo's dapper clothes take a

beating over the course of the films and they acquire all sorts of dirt

and tears. The wardrobe team has six versions of Bilbo's adventuring

outfit for various points in the film (as well as smaller copies of each

for Freeman's scale double). Apparently, it does not go well for

Bilbo's lovely jacket.

The

Dwarves, for their part, get a lot of leather. So much, in fact, that

one member of the press asked Buck, "Is there any leather left in New

Zealand?" Buck described the Dwarves as "blokey" and "almost like a

biker gang in a way." Still, the costume department had to come up with

looks that reflected their life and status. Kili (Aidan Turner) and Fili

(Dean O'Gorman), as Thorin's nephews are of a noble line, while Balin

is more of a lordly councilor and Dwalin a general. Gloin would be a

high-ranking military officer and Oin the medical practitioner. Stepping

down a caste, Dori, Nori, and Ori would be more of a merchant class.

The

costumers also designed graphic motifs for the Dwarfs (I felt like some

of them resembled mechanical Celtic knots), stamped them on leather, and

created their own fabrics with the motifs in them. Every component of

the outfits, every button, every buckle, is originally made for the

films.

The tricky

things about the Dwarves' outfits are the fit and the weight. All of the

Dwarves wear some form of padding—even Kili has some artificial meat on

the shoulders and thighs—and it sometimes behaves in unpredictable

ways. Buck mentioned one outfit that made the big-tummied Bombur look

like the Michelin Man. And the one complaint the actors playing the

Dwarves had was the amount of gear they have to carry; after months on

set, it can get pretty exhausting. Buck indicated that Thorin and Bombur

probably have the heaviest outfits (Bombur's is mostly girth suit), at

perhaps 89 pounds.

Incidentally, Bofur may have the best hat in all of media. Sorry, Jayne Cobb.

World Rebuilding

Production designer Dan Hennah said that he feels like the visual scale of The Hobbit is larger than that of Lord of the Rings in some ways:

You have to think of it a little bit as a road movie. They leave Hobbiton and they go to the Lonely Mountain, and they come back to Hobbiton, but we're never anywhere for very long. It's one of those continuous changing faces everywhere you go. And, of course, every part of it is a different culture, and so it's demarked into different propage and different costumes.

The Art Department's rule is, according to Hennah, "The concept art starts with Tolkien." When designing scenes for The Hobbit, the department would continuously return to Tolkien's own illustrations, and in some cases, they had Lord of the Rings designs to work with. The Hobbit

will take us back to Rivendell, but it won't be quite the same

Rivendell we saw before. Henneh notes that, when last we saw Rivendell,

it was in the autumn of the Elven civilization. For The Hobbit, they're giving it a more uplifting, mid-summer feel, adding a bit more color and magic.

Dale is the

largest set constructed for the film, and we'll be seeing Dale both

pre-Smaug (which we don't get to see in the book) and post-Smaug.

Pre-Smaug Dale will emphasize the city as an orchard city, with a

fairgrounds feel, filled with fruit trees, grape vines, and raspberry

bushes. But the team also identified it as an alpine city, with water

flowing through it, giving it a somewhat Venetian feel. The teams wants

to portray what day-to-day life was like in this version of Dale, right

down to the fabrics people would wear on a Sunday afternoon.

In contrast to Dale and Rivendell, we'll also take a tour of the Goblin court in the Misty Mountains. Henneh describes it:

It is a trap in the cave in the Misty Mountains, of course, and then once you get inside the Misty Mountain, it's like if you can imagine big internal crevasses that are just basically run right through. They're not just little round caves. Huge, big diagonal rips in the mountain. And so in amongst that the goblins that have stolen, they're like scavengers, they steal and they find, so they've got all this timber and fabric and skins, and this little kid's tree house, but they just cluster all over this thing and right in the centre of it, on a little pinnacle, is the goblin king's throne. Which is made out of an old bedstead ripped in half and turned upside down, and he sits on the head of the bed.

The team

had a lot of fun creating the Misty Mountains. Set decorator Ra Vincent

describes art department members gleefully making goblin hats and Henneh

added that he particularly appreciated the tarantula kebabs.

Turning Men into Dwarves

Expand

Expand

Dwarves

have big foreheads, big noses, and ears that stick out for forever.

Fortunately for the actors, great strides have been made in the area of

prosthetics that let them spend less time in the makeup chair. Weta

designs and makes the prosthetics, and then they're painted and applied

by Tami Lane and the rest of the Stone Street prosthetic makeup team.

During the filming of Lord of the Rings, John Rhys-Davies had

to wear a certain type of silicone prosthetic that needed to be blended

off with gelatin eye bags to complete his transformation into Gimli. He

had to spend in the neighborhood of three and half hours in the chair,

and because the gelatin quickly melted, the prosthetics required

constant maintenance.

The new

silicone flat gel, developed in the last five or six years, is

encapsulated in a theatrical bald cap material that's much easier to

paint and apply. And, according to Lane, "[I]t's virtually heat-proof,

water-proof, fire-proof, hurricane-proof." Just in case you ever felt

like setting a Dwarf on fire. How much easier is it? It takes just an

hour to give Richard Armitage Thorin's face. Even Bombur, who has a chin

prosthetic, cheek prosthetics, and a bald spot, takes an hour and three

quarters to make up. Kili, who has only a nose prosthetic, gets off

easiest with just 20-30 minutes of makeup. Even so, the prosthetics

themselves require a lot of love and care. After a day of shooting, a

prosthetic can't be reused, and each one needs to be hand-painted with

each eyebrow hair hand-punched. That's a lot of detail work with tiny

hairs.

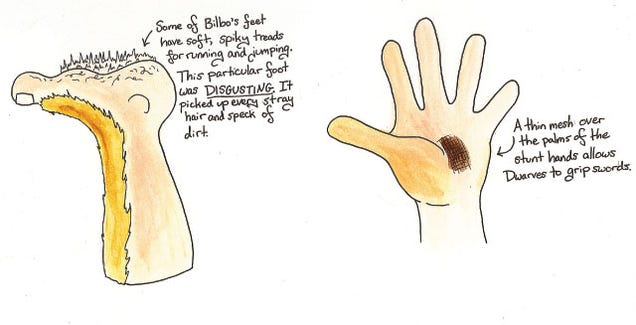

There have been similar advances in Hobbit foot technology. In the Lord of the Rings

days, the makeup team had to glue foam latex feet to their actors'

feet. Now the studio has slip-on Hobbit feet—just add baby powder and

food. Martin Freeman wears insoles with his feet and he can even

manipulate the toes. When his feet are being shot from below, Freeman

wears feet with natural-looking soles. When he's running or jumping, he

wears feet with little spiky treads on the bottom for traction. Perhaps

in the next iteration, they'll make them grime-repellant; the Hobbit

foot passed around the room became a magnet for every particle of grit

and stray strand of hair in the room.

In addition

to their facial prosthetics (including fake ears that slip over their

real ones), the Dwarves wear Dwarf-proportioned hands. The full hands

aren't particularly practical for axe-wielding, but stunt hands don't

have a full palm; instead they have a meshy layer over the palm that

lets actors grip their weapons without pesky slippage. Thorin is the

only Dwarf who gets full arms since he's sometimes filmed with his

sleeves rolled up. Petite Lane slipped a disconcertingly realistic

Thorin arm over her real one while we marveled at her suddenly wrong

proportions.

An

interesting aspect of the new Epic cameras led to a slight tweak in the

prosthetic makeup. When you see one of the Dwarf actors in person, he

looks slightly flushed in some places. It turns out that the Epic

cameras recognize yellow more intensely than the human eye does, forcing

the makeup team to pinkify their prosthetics in order to compensate.

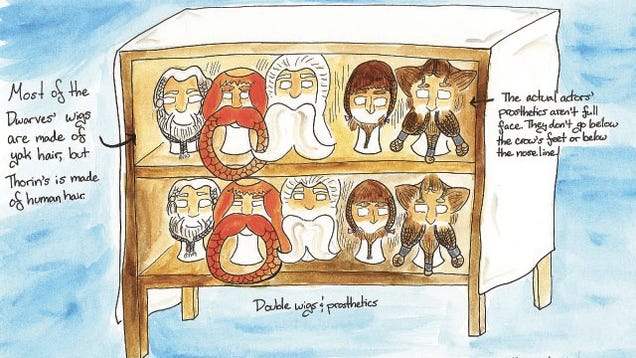

Haste required many of the actors in The Lord of the Rings movies to wear synthetic wigs, but the wigs in The Hobbit

are hair—though not necessarily human. The Dwarves have yak hair wigs

and beards to achieve a coarser effect—all except the regal Thorin,

whose wig is made from human hair.

The wigs

are made by a wig maker in the UK, which can be pricy (a certain wig in

the trilogy cost $5,000), but allows for multiple versions of custom

designs. Each character has at least three sets of wigs—one each for the

actor, stunt double, and scale double (who's the same height as the

character). According to hair designer Peter King, the Dwarves have six

wigs and eight beards; the extras are for filming in certain situations.

Striking

the right balance with the prosthetics and hair could be tricky in the

design stages. Each character would have to get in full costume, full

hair and makeup, and get in front of the production team and then in

front of a camera. Often, they found that what looked good on the page

didn't work on camera, and they would got through five, six, seven of

these "show and tells." King said Thorin was the most difficult

character to nail down; they wanted to be certain that he was conveying a

leader-like quality, and the decision to switch from yak hair to human

came out of one of these "show-and-tells." Other characters came with

their challenges, but Thorin went through the most hair and prosthetic

changes. Lane added that they ended up simplifying the design in the

end, making his nose smaller and his forehead less pronounced. But even

before they got to the "show and tell" stage, there were often

mind-boggling numbers of design iterations. McTavish said that 819

different illustrations were made of possible beards for Dwalin.

Filming 13 Dwarves, one Hobbit, and Ian McKellan

One thing

you will notice as soon as you walk into Stone Street Studios is that

there are massive green screens everywhere. You can take tours of the

real-life places where Lord of the Rings was filmed, but The Hobbit is a largely indoor affair. Where Lord of the Rings was a masterpiece of forced perspective, Jackson opted to try something different this time around.

To film Bilbo, the Dwarves, Gandalf, and the other characters at their respective heights, The Hobbit

employs slave motion capture technology, specifically SimulCam. For

example, when Gandalf is talking to the Dwarves and Bilbo in Bag End,

the Dwarves are over on the set, and Ian McKellan is on a sound stage

standing in front of a green screen. The camera filming Ian McKellan is

"enslaved" to the camera on the Bag End set so that both cameras are

looking the same way relative to their positions. McKellan's performance

would then be superimposed onto the Bag End footage.

McKellan,

for the record, hated this. He would be alone on the green screen set

talking to tennis balls on sticks set at the height of a Dwarf's eye

line. He says he was so vehemently against the slave cam that Jackson

ended up cutting down on the number of scenes that employed it.

What is the deal with 48 frames per second?

The set visit took place just a few weeks after the first screening of Hobbit

footage at 48 frames per second, and there was a lot of curiosity about

why Jackson planned to release some versions of the film at such a high

frame rate in 3D and what other folks working on the film thought about

it. Most of the actors had no particular opinion on the frame rate and

confessed to not really liking films in 3D.

When asked

why he planned to release the film at 48 fps in 3D, Jackson's reply

indicated that this is largely an experiment to see how people react to

that format as an immersive viewing experience. After noting that camera

resolutions are getting higher, projectors are getting brighter, and

screens in some places are getting larger, Jackson asked, why not try

moving beyond the old familiar frame rate?

And it's really a question of do you just say, "Okay, this is what we've been used to for the last seventy-five or eighty years, and that's what we're going to stick with." Or do you explore ways to actually harness this technology to give people a better experience, and we're also, as an industry, we're facing a situation where less young people, especially, are coming to see films anymore. It's too easy to watch them on your iPad. Too easy to stay at home and play games, and so I think anything that we can do to provide a more immersive and spectacular experience—Filmmakers have been doing it, sixty-five mil, 2001, Kubrick and David Lean, they shot in these huge big formats to try to make it sharp and clear and that was like the equivalent of five-K in the film stock days. Todd-AO was 30 frames a second, wasn't it, for Around the World in 80 Days. There's been people trying to push it, but of course the just effect for seven or eight decades projectors were pretty much locked into twenty-four frames per second. We had to get past the mechanical film age to be able to explore other things, but it will be interesting. I personally think 48 frames is great, but we'll just wait till everyone can just see a whole full length movie, graded and timed and we'll see what people think.

For

everyone else, 48 fps has meant a lot more work. Peter King noted that

the hair and makeup department had to learn what the new cameras see and

adjust their designs accordingly. Dan Henneh explained that the

increased depth of field forced the art department to include more

detail in their designs; Ra Vincent added, "It's actually enriched the

propage and the sets a whole lot more, I think, because we're quite

often using real materials instead of prop making plastics and things."

Simon Bright, another member of the Art Department, concurred, "Gone

were the days where you could say, 'Aw, that's just background, we won't

have to worry about that too much.'" Matt Aitken pointed out that 48

fps means there need to be twice as many frames of any animated

sequence. There has been a lot of time invested in this experiment, but

fortunately we only have to wait a few weeks longer to see how that

experiment pans out.

http://www.wetanz.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment